The Perfect (?) Musical Libretto Format

No Standard(s)

As an art form, the Broadway-style musical is upwards of a hundred years old. (Show Boat is nearly ninety, and while it certainly broke new ground, it was hardly The First Musical.)

Yet in all that time, with the thousands upon thousands of musicals that have been written, performed, and published, the industry has yet to settle on a standard format for the libretto (the published “script” containing all spoken dialogue and sung lyrics). And I’m not just talking about subtle differences like font size or margin width — I mean fundamental issues like whether the words are centred or left-aligned, roman or italic, uppercase or mixed case. (Stage plays suffer, to a much lesser extent than musicals, from a similar lack of an industry standard.)

This surprising fact stands in stark contrast to cinema, an art form of roughly the same vintage as the modern stage musical, but one in which a well-known, highly-specific, industry-standard format for screenplays has been in place for quite some time. That format is so fine-tuned, even the font choice is set in stone.

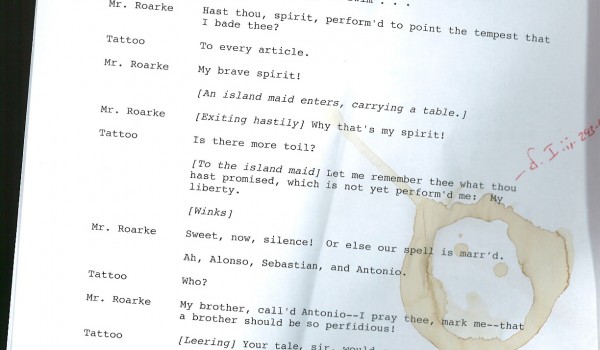

While typesetting the librettos for my three stage musicals (Fairy Tale Ending, ToboR the RoboT, and Robin Hood: The Legendary Musical Comedy), I’ve been studying the various formats used by other writers and publishers. In the process, I believe I’ve found the best possible solution to the main problem presented by the form.

Two Types of Dialogue

The primary issue, of course, is that a stage musical contains [at least] two types of “dialogue”: spoken and sung. The typesetting must make it immediately clear which is which.

In the format which currently lays best claim to being the de facto standard, sung lyrics are centred and capitalized. Putting aside the well-known fact that text set in all uppercase is more difficult to read than text set in sentence case, in the 21st Century we have the added drawback that all-caps is the typographical equivalent of shouting. (Come to think of it, that might explain some things about certain musical theatre performers…)

Consider, for example, Page 6 of the libretto of Lucky Stiff (Book & Lyrics by Lynn Ahrens, Music by Stephen Flaherty, published by Music Theatre International). There are at least five different types of information on the page, doing five different things — song title, character name, spoken dialogue, sung lyrics, and stage directions — but the page is a typographical (and hence comprehension) nightmare.

Compare this version, set in the format I’ve recently settled on. In both cases, the spoken dialogue is flush-left and the sung lyrics are centred; since (in my opinion) this alignment adjustment sufficiently distinguishes the two, my format leaves the lyrics in sentence case, thus avoiding the less readable (and nowadays “shout-y”) all-caps. By setting the song title in bold underlined uppercase, and the stage directions in flush-left lowercase italics, those two types of information have their own distinctive look and feel, which encourages faster scanning, interpretation, and comprehension by the reader. And by explicitly stating the character’s name, in bold uppercase, to the left of spoken dialogue and centred above sung lyrics, the speaker/singer is always clear to the reader. Page 24 of the Lucky Stiff libretto, on the other hand, provides a good example of what not to do in this regard: the format chosen (character names centred between left-aligned lines of dialogue) forces the reader to scan across the page over and over just to link a character with each bit of dialogue.

Towards an Industry Standard for Musical Theatre

The film industry learned early on in its evolution that adopting a standard format would reap many benefits for writers, producers, actors, and directors alike. For writers, the standard format helps level the playing field: it becomes “transparent” and intuitive to readers and producers, so the content can shine through without having to fight the presentation. For producers, having a standard format helps identify experienced writers (who know to, and know how to, use the format), and even affords a quick (and remarkably accurate) estimate of the duration of the film based solely on page count. For actors and directors — indeed, any creative artists involved in film production — a standard format provides a consistent and comfortable way of parsing out relevant information from the script, as efficiently as possible.

Personally, I would love to see the musical theatre industry develop, discuss, and ultimately adopt a standard for librettos based on established facts about typography and comprehension. I’d be happy to offer mine (seen here, in the first four pages of Fairy Tale Ending) as a starting point.

Pingback: Friday, December 4 | Assignment Blog